|

Frances Noble talks to Joe Flack

about his transient cityscapes

I love looking at your pictures, they seem to take place in four dimensions, coming out of the canvas and running across the frame – or even using materials to jut out from the plane of the picture and invade the viewer’s own space. Why do you do that?

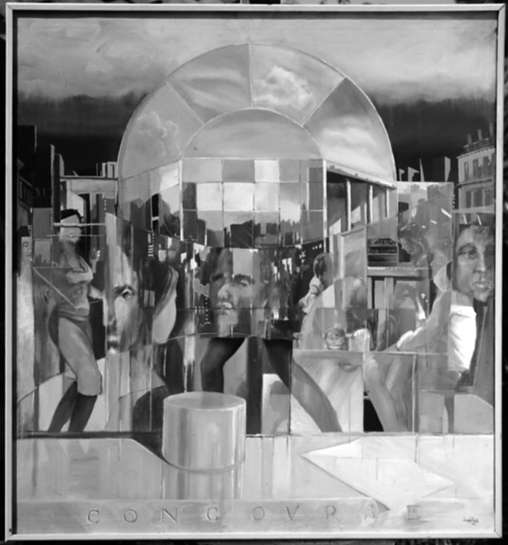

That’s a very important aspect of my work for me. I’m not a cubist but I do agree with much of the cubist philosophy. Seeing things as they exist in space and at all times rather than from a fixed point of view; changing my viewpoint as I look at a subject. I think we see things in layers – as an amalgam of the impressions we receive when we journey past them – just glimpses of the experience which would be knowing the things themselves. When I paint a canvas I sometimes cut it up and shift the parts to distort and confuse the viewpoint. I sketch in the form, and as I work the details appear and determine themselves. The paintings take shape bit by bit as I build up and scrape away paint moving elements of the composition backward or forward in a constant state of flux. I work to and beyond, the flat surface of the canvas or the limiting edge of the frame and destroying those edges is part of the pleasure I get in making my pictures.

I find it almost impossible to decide when a piece of work is finished. But eventually I do come to some sort of state when I can leave it alone. If it stays in the studio though, I’m quite likely to start work on it again at some stage – it’s probably a good thing if I lose contact with the work. Do you know the stories about Cezanne? He used to smuggle paintbrushes and paint into galleries where his work was exhibited, so that he could alter and finish passages. If the gallery knew he was coming they would hide his pictures!

Some of your views through train windows look like film, with rectangles of the whole image divided into frames by the train windows.

Because I don’t drive, whenever I go anywhere I either get a lift or I’m on a train and that gives me a freedom to see the landscape or cityscape as I move through it. I create an impression on my canvases from those passing images and the film-like effect is a consequence of the way I actually see and recall images.

Most of your pictures seem very urban, yet you live in the heart of rural Norfolk. How did that come about?

I was born in London and lived there for 36 years. When I came to Norfolk I found I missed London terribly. So, although while I was living in London I used to go out into the Surrey countryside to paint landscapes, once I had moved, I seemed able to paint only London scenes. So many people here in Norfolk seem to paint landscapes that it all seemed to have been done before. It was the memories and recollections of London that I wanted to paint most strongly. Though I’m getting round to landscapes myself now, after 20 years. My first Norfolk landscape shows the side of a fertiliser tank with rust, crackled paint and bitumen! I studied Architecture and Design and I love the way man-made things contribute to landscape. I’ve never practised as an architect though and I have been painting as long as I can remember.

Are you still making pictures from those 20-year-old memories?

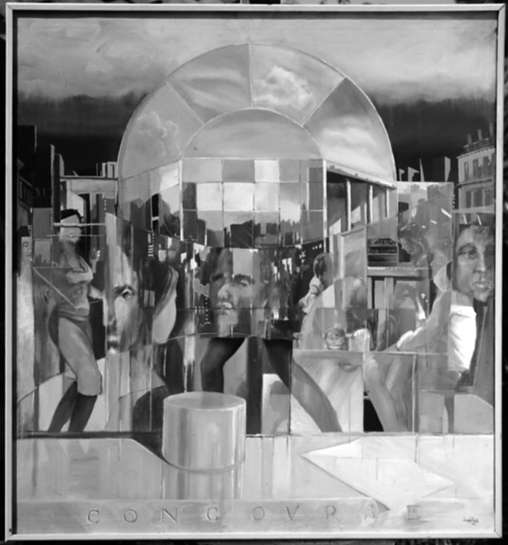

I need to return to London several times a year, and I walk miles and miles, just looking and mentally recording the things I see. The curious thing is that when I first came to Norfolk my pictures were all of urban interiors and relatively static. Now I seem to be painting the city from a condition of transience – as someone passing through – a traveller. That’s why things like a railway concourse or the view from a train window appear so often in my work. Even so, none of my urban pictures are painted from life but are based on memory. I admire Whistler for his ability to do that. I play a game with myself – looking at a scene and then turning my back on it and describing what I have seen to someone who can still see it. It’s surprising how accurate I can be. Making my pictures is about editing and combining memories and recollections to give the finished picture form and structure.

Concourse by Joe Flack

Do you visit galleries and enjoy looking at other people’s work?

Oh yes. I have a special gallery technique. I walk at slightly slower than normal walking speed round the whole thing and a couple of pictures may ‘tap me on the shoulder’ as it were and I will look just at them. That way I’m always surprised by something which I may never have noticed before. For example I was walking round the Rijks Museum in Amsterdam with a couple of friends (also painters) and out of all those marvellous pictures the one which totally captivated me was of a white swan coming towards the viewer, out of the picture. The paint treatment was amazing, the softness of the feathers and the light shining through the beak making it translucent. A simple subject made immensely noble.

Am I right to think I can see references to and quotations from other works in your paintings?

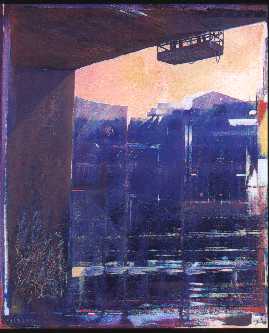

I love making references to previous works, although I never overtly copy. For example in a recent picture,

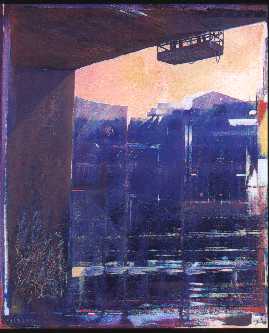

Painting by Joe Flack

which is perhaps a building site near Clapham Junction (certainly I used to spend a lot of time there) there is a painter’s cradle hanging down under the frame of the building, and the idea for that comes from the Canaletto picture of the building of Westminster Bridge, where he shows a bucket suspended under the arch of the bridge.

Westminster Bridge by Canaletto

I liked the way it divided up the arch in the structure of the picture and destroyed the symmetry of the arch. But as well as that, the idea brought together a series of unrelated memories. Painting a backdrop at Wembley suspended 80 feet above the ground in just such a painter’s cradle! That’s the sort of thing I mean when I talk about an amalgam of memories.

Does that mean that memory as recollection of event and emotion and memory as recollection of visual are always intertwined for you?

Yes it does. Whenever I go back to places, however permanent they have seemed in the past I find that they have changed. I had a really strange experience once. When I was a student I had a poky little room in a house in Fulham. Two years later I was walking down that same street and they were demolishing the house. Just as I got there they knocked down the front wall, and there was my room. Exposed. With the tacky wallpaper and the brighter rectangles where my pictures had stopped the pattern from fading, dangling, as it were, in time and 20 feet up in the air. Ten minutes earlier and I would have noticed nothing unusual, ten minutes later and my room would have gone completely. That was a seminal experience for me, of impermanence and the importance of memory. So my pictures are a way of making a personal recording of the one-time existence of things.

My architectural training means that I have no difficulty in accepting that all building is impermanent. But even so I was moved and amazed by that experience with my old room. Timing and a sense of fleeting images is always part of my paintings. Whenever I go back to places I have known I see changes. It’s only our attitude to property and ownership that makes us imagine that buildings can be permanent elements of our landscapes and lives; it’s the material value we place on buildings which makes us see them as fortresses which should stand for ever.

Some of your most fragmented urban scenes contain figures or faces. Are those ‘from life’?

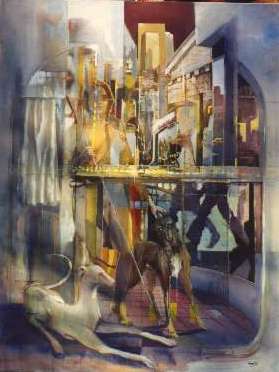

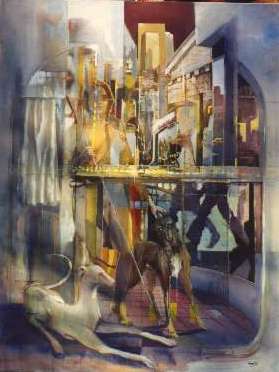

No, not at all, they are constructs, drawn from memories and quotations from other pictures. For example in Diana, I painted classical references – the naked figure (both goddess and a modern, real woman) and the two dogs which she holds stand in a quarry. But they are seen reflected in and through the glass of office buildings. Then the classical portico with just the letters NA visible – could be . . . TIONAL WESTMINSTER BANK or . . . TIONAL GALLERY just something very formal and institutional that could have been built from the stone of the quarry. Playing with these ideas of time and space was what interested me not the specifics of a particular young woman.

Diana by Joe Flack

How do you feel about working to commission?

I used to like that commitment to a piece of work, but not so much these days. I tend to start out eager to please the client and find that part way through the picture wants to take me in another direction. Now I’m confident enough to say ‘I will take these elements which you want incorporated, but you will have to trust me to work out the problems the picture poses in my own way.’ I believe that I should have the ultimate control over the making of the picture. I don’t believe that in an ideal world artists should work for other people or for money but for their own satisfaction. That’s easily said, but in the past I have painted pub-signs and I still do the occasional book jacket to earn a living.

What do you think of the current state of modern art in this country?

I’m not at all unhappy with what’s going on, unlike some of my contemporaries. Painting isn’t dead, it may be resting but it will come back. There is this criticism of artists like Tracey Emin and Gilbert and George, who have based their art on their own personalities, and I wonder whether, despite all the hype, their work will retain its value. I have my doubts – the history of art is littered with people who were once popular but now hardly remembered. On the other hand, they are breaking new ground and making people think, and that must be a good thing. I really like Rachel Whiteread’s work using translucency to play with our preconceptions of solidity and space. I’m not completely against Brit-Art. When Damien Hirst cut his calf in half, my reaction was that Rembrandt and Chardin would have loved that – the precision of revealing the innerness of things. The Romans showed things like that in mosaics, the idea isn’t new, only the method. So you see I’m not as depressed about the future of art, in fact I think you could say I’m quite optimistic.

I have got to a state where I am confident enough about my own work to enjoy the real pleasure of someone who is touched by something I have made. So I don’t feel threatened by the new successes. For some artists their distrust and anger at the new art is at least in part about money – a kind of financial jealousy. But the price that some modern works can realise is a function of the market, more than the skill and creativity of the artist/maker. The main difficulty with most of the modern art we’ve been discussing is to consider whether anyone would buy it – the Saatchi Collection notwithstanding. Throughout history great collectors have indulged themselves in the modern and extreme without any certainty of a return on their investment, there’s nothing new in that.

My own measure of successful work (mine or anyone else’s) is that the piece should create its own mood and atmosphere. A good painting should attract you and draw you in, enriching you. So that you leave it feeling slightly more knowledgeable than you were.

Distancesby Joe Flack

What about the stage backdrops which you paint – are they a pleasure to make or a chore which pays the bills? How did you get involved in doing those?

It was total chance, and quite a long story! It all began in London many, many years ago. I was in a pub with a friend and was approached by a photographer’s agent who had realised I was a painter; he asked if I could paint a tree about six foot by three feet and with a little background. Of course I said that I could. It turned out to be for David Bailey for a photo shoot for the Milk Marketing Board. It was about 10 pm when this happened and I went straight to Bailey’s studio and worked all night, in the morning there was the tree they wanted. Soon I was getting more commissions for the same sort of work, and for murals for restaurants in the West End. I loved painting on such a large scale. It made me realise how much I had always been attracted to big paintings. I remember, as a child, walking with my father past a cinema in the West End and seeing the huge portraits of Humphrey Bogart and other film-stars, their faces eight feet high on billboards above the cinemas where their films were showing.

Oddly enough one of the companies which makes backcloths and props for staging and concerts, Hangman, is based in the part of Norfolk where I live; someone noticed one of my photographic backdrops and commissioned me to paint the stage backcloths for Tina Turner’s first Farewell Tour. I’ve done four of them now! They asked me to make this set in monochrome so that they could change the set with coloured lighting. In fact the huge (100 feet by 30 feet) cloth was such a success that it wasn’t colour lit at all. It was a very abstract work, created freehand with spray guns using black, white and grey paint, and took two of us several days to do. We completed the cloths by splattering them with silver paint. It was an exhilarating, messy process and by the time we were done we were exhausted by the adrenaline rush that had seen us through.

Nothing else can produce the excitement of working on that sort of scale. I’ve made quite a name for myself now, and avoid the problem of highly prescriptive commissions. Some producers say ‘Oh, it’s Joe, just let him do his own thing!’ which is great. I’m famous for not sticking to the brief anyway, but rather working in my own way. I’ve done loads of these things now – apart from Tina Turner – the Spice Girls, Phil Collins, Hear’say, Freddie Mercury’s Aids Concert and Party in the Park. Even the Chippendales! That was a weird experience. I wasn’t allowed to watch the show (no men are ever allowed in) and I had to ask my wife to report back to me on how the set worked.

I love the thrill of the last 12 hours before a show opens, when it’s all coming together so fast, and I’m working at the top of the gantry finishing the cloths while the sound checks and lighting scripts are being done. It’s noisy, chaotic and very tense but it is always ready on time, however impossible that may seem at the time.

Surely the same lack of permanence and lasting financial value which

you predict for much modern art could be made about your backcloths. Does it bother you that they are on display for such a short time?

People always ask me what happens to the cloths after the shows and how I cope with the idea of my work being thrown away. But to be honest by the time they have been on tour, and been put up and taken down all over the world, they are pretty much finished and worn out. Perhaps it’s easy for me because of that concept of the impermanence of things that I spoke about earlier. I see the backcloths as part of a team production, very different from the rest of my work, which can be very solitary. They are, like the music itself, part of the performance. I like that, being an integral part of the whole thing, part of a collaborative process. I don’t expect them to last for ever.

|